A Longitudinal Study of Domestic Canine Behavior and the Ontogeny of Canine Social Systems

Semyonova, A, 2003, The social organization of the domestic dog; a longitudinal study of domestic canine behavior and the ontogeny of domestic canine social systems, The Carriage House Foundation, The Hague, www.nonlineardogs.com, version 2006.

Abstract

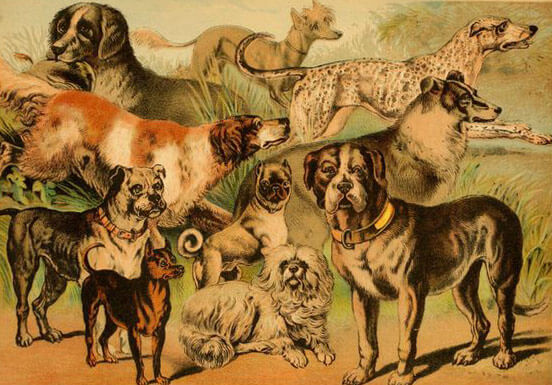

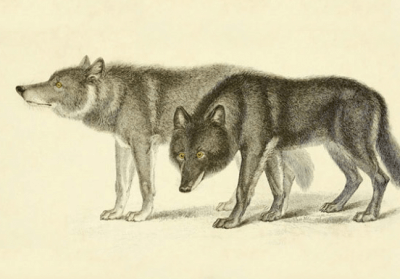

The theory that a hierarchy based on dominance relationships is the organizing principle in social groups of the sort canis lupus is a human projection that needs replacing. Furthermore, the model has unjustifiably been transferred from its original place in the discussion of the behavior of wolves to the discussion of the behavior of domestic dogs (canis familiaris). This paper presents a new, more adequate model of how familiaris organizes itself when in groups. This paper is based on a longitudinal study of a permanent group of five randomly acquired dogs living in their natural habitat, as they interact with each other within the group, with newcomers of various species who joined the group, and with fleetingly met individuals of various species in their outside environment. This study shows that the existence of the phenomenon “dominance” is questionable, but that in any case “dominance” does not operate as a principle in the social organization of domestic dogs. Dominance hierarchies do not exist and are in fact impossible to construct without entering the realm of human projection and fantasy. The hypotheses were tested by repeatedly starting systems at chaos and observing whether the model predicted the evolution of each new system. The study shows that domestic canine social groups must be viewed as complex autopoietic systems, whose primary systemic behavior is to gravitate as quickly as possible to a stable division of the fitness landscape so that each animal present is sitting on a fitness hill unchallenged by other group members. Aggression is not used in the division of the fitness landscape. It is not possible for an observer to measure the height of respective hills. There is no hierarchy between or among the animals. The organization of the system is based on binary relationships, which are converted by the agents as quickly as possible from competitive to complementary or cooperative binaries, through the creation of domains of consensus. The production processes by which this is done are twofold. The first is an elegant and clear, but learned, system of communicative gestures which enables the animals to orient themselves adequately to each other and emit appropriate responses in order to maintain or restore the stability of their fitness hills and the larger social landscape. The second is learning. It is the learning history of each animal, which determines how adequately the animal can operate within the system and what the components of its individual fitness hill will be, and which, in the end, is more crucial to the animal’s survival than even presumed genetic factors or some human-constructed “dominance” position.